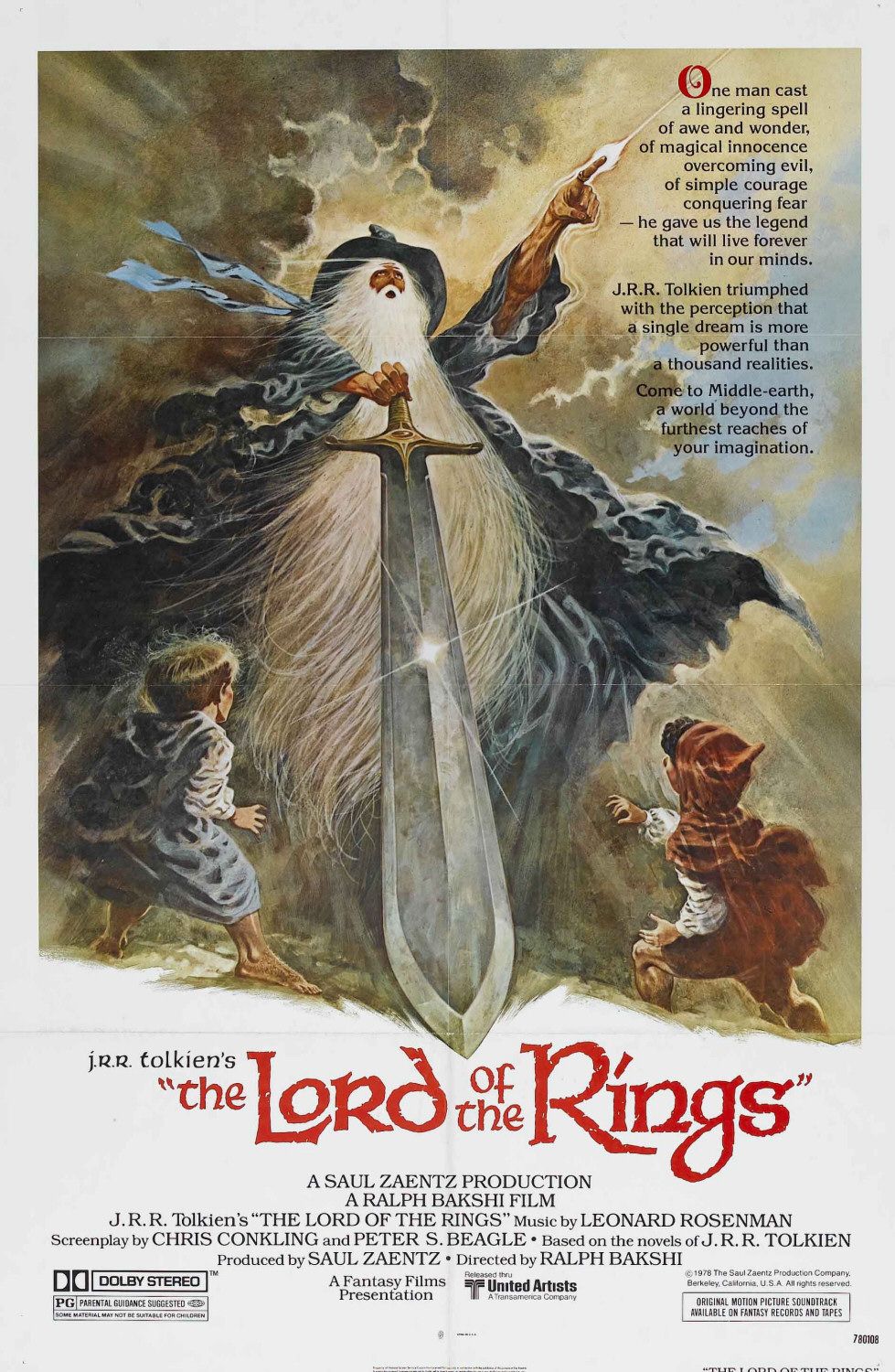

Tolkien Before Jackson Part 4: The Lord of the Rings (1978, Directed by Ralph Bakshi)

Note: For more on the famous alleged Tolkien quote on the poster for the 1978 Lord of the Rings movie, check out this post.

Ralph Bakshi holds a curious place in animation, because he is important no matter what people think about his films.

As Tom Tataranowicz noted in the documentary Forging Through The Darkness: The Ralph Bakshi Vision, Bakshi started making animated films in a dark time. Between Walt Disney’s 1966 death and the 1989-1999 Disney Renaissance, the Disney company floundered. Budgets mattered more than good product. Innovative animators like Tim Burton and John Lassiter got fired for being too innovative. Beyond that, as Bruce Timm and others report in the documentary The Heart of Batman, 1980s parental censorship encouraged animators (outside or inside Disney) to keep their work tame. It was a bad time to be someone like Bakshi, making R-Rated animated films on topics like racism (Coonskin) or the immigrant experience (American Pop).

The early 1990s finally ended this period. Timm and colleagues (several of whom got their early breaks working for Bakshi on the cartoon show Mighty Mouse: New Adventures) revived American TV animation through shows like Batman: The Animated Series. Pixar finalized a team that created groundbreaking films like Toy Story. Bakshi had nearly retired by this point, although he achieved one last innovation in the late 1990s: the strange cyberpunk TV show Spicy City, which beat South Park by a month to become the first American TV show exclusively marketed to adults.

All of this means that Bakshi made The Lord of the Rings and other films as best he could in a fallow period. They may be flawed, but they were innovative at a time when innovation frequently got disregarded.

Therefore, it is not surprising many say that Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings is not entirely successful but still important. Time Out included it as a qualified entry on its list of the 50 greatest animated films: “The film remains a noble failure but the fact that these images stick in the mind even after repeated viewings of Jackson’s towering achievement is a testament to Bakshi’s imagination in bringing Middle Earth to life.”

Many of the images certainly do stick in the mind. The animation mixed several media—the opening prologue communicates the ring’s backstory using pantomime actors behind a red screen.

The main narrative is traditional animation with rotoscoping (live-action footage converted to animation frame) for the characters. Optical effects appear in the magic sequences like Saruman taking Gandalf prisoner.

Sometimes the rotoscoping works, and other times it just makes things strange. It makes the characters more fluid than the backdrops, which I enjoy in other Bakshi films (say, American Pop). Perhaps because this is a fantasy film, the method just feels disconcerting here. A journey into the Uncanny Valley. Strange effects in a strange world can be a step too far. However, the uncanniness works when the Black Riders arrive, making them truly otherworldly.

Now, some may argue the various animation styles is meant to be psychedelic. Bakshi made this film in the 1979s, after all. I would argue the strange visual mix looks more like cost-cutting than deliberate strangeness. For comparison, consider the strange 1980 anthology film Heavy Metal (the inspiration for the Netflix series Love, Death, and Robots). Heavy Metal is a gleefully mishmashed anthology of fantasy, sci-fi, and horror stories. Some stories are coherent. Others not. Many stories feature strange or gratuitous content (not unlike the content in Spicy City). To make matters more complicated, the animation style changes in each story.

Yet Heavy Metal makes sense on its own terms. It has plenty of odd and objectionable elements, but it wants to be odd. Furthermore, it knows it has to be odd because the material (late 1970s-early 1980s weird speculative fiction) demands it. It’s offbeat and proud of it.

Bakshi inserts some offbeat energy but doesn’t put it front and center. Viewers keep looking for the impish weirdness so present in his urban films (Fritz the Cat, Heavy Traffic) or his later fantasy films (Wizards), and come away disappointed.

For all the flaws, Bakshi does get one thing right. Of the projects discussed in this series, Bakshi’s film comes the closest to a cinematic take on Tolkien’s material. Others are interesting. But few of them have a sense of grand scale and wonder that feels like a film, not a children’s show or TV movie. At its best moments (particularly the Battle of Helm’s Deep), Bakshi’s film achieves the wonder that fans wouldn’t see until Peter Jackson came along in 2001.

The fact that Bakshi released this movie in the late 1970s, just a year after Star Wars and just before the fantasy/sci-fi movie craze, is also notable. It’s inconsistent, but its inconsistency shows how much the rules for making a fantasy film were unwritten at the time.

The next decade would see many more experiments—from animated films like The Black Cauldron to live-action genre deconstructions like The Princess Bride. Some films worked. Others failed miserably. Bakshi’s fantasy projects (Lord of the Rings, Fire and Ice, Wizards) fit solidly in the middle: flawed but always memorable. At their worst, casualties of a genre that hadn’t figured itself out yet.

Come back next week when we talk about the Russian adaptations of Tolkien’s work.

1 Response

[…] had to be as tame as Super Friends. Censorship, Reagan-era conservatism (and some other factors I discuss in an article for The Tolkienist about Ralph Bakshi) kept animation feeble until the early 1990s. Tim Burton’s Batman in 1989 […]