Tolkien Before Jackson Part 3: The Rankin-Bass Adaptations

While Rankin-Bass is best-known to American audiences for their Christmas TV special Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer, the company also produced a number of traditional animation films. Fantasy film experts may remember their adaption of The Last Unicorn from the novel by Peter S. Beagle.

The company also produced two animated movies based on Tolkien works, which will be discussed together.

The Hobbit (1977, Directed by Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass)

Perhaps the most mainstream and well-known adaptation of The Hobbit before Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy, this movie is interesting but lackluster.

Some acting choices (John Huston as Gandalf) work quite well. Others (Otto Preminger doing a bizarre accent as the Elvenking) are confounding.

Looking at it now, what perhaps stands out the most is the animation looks halfway between cultures. In the first post in the series, on Gene Deitch’s The Hobbit, I mentioned it combines an American director and an Eastern European artist working together. We get an even stronger sense of cultures collaborating here: Asian animators working with American direction, so the animation feels not quite Western, not quite Eastern.

In fact, the animators on this film later contributed to some very famous Eastern animation. Rankin-Bass commissioned the work from Japanese studio Topcraft (who worked on several other Rankin-Bass Productions, including The Last Unicorn). Topcraft worked with Hayao Miyasaki in 1984 to produce Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. After Topcraft folded in 1985, its members became the basis for Miyazaki’s acclaimed Studio Ghibli.

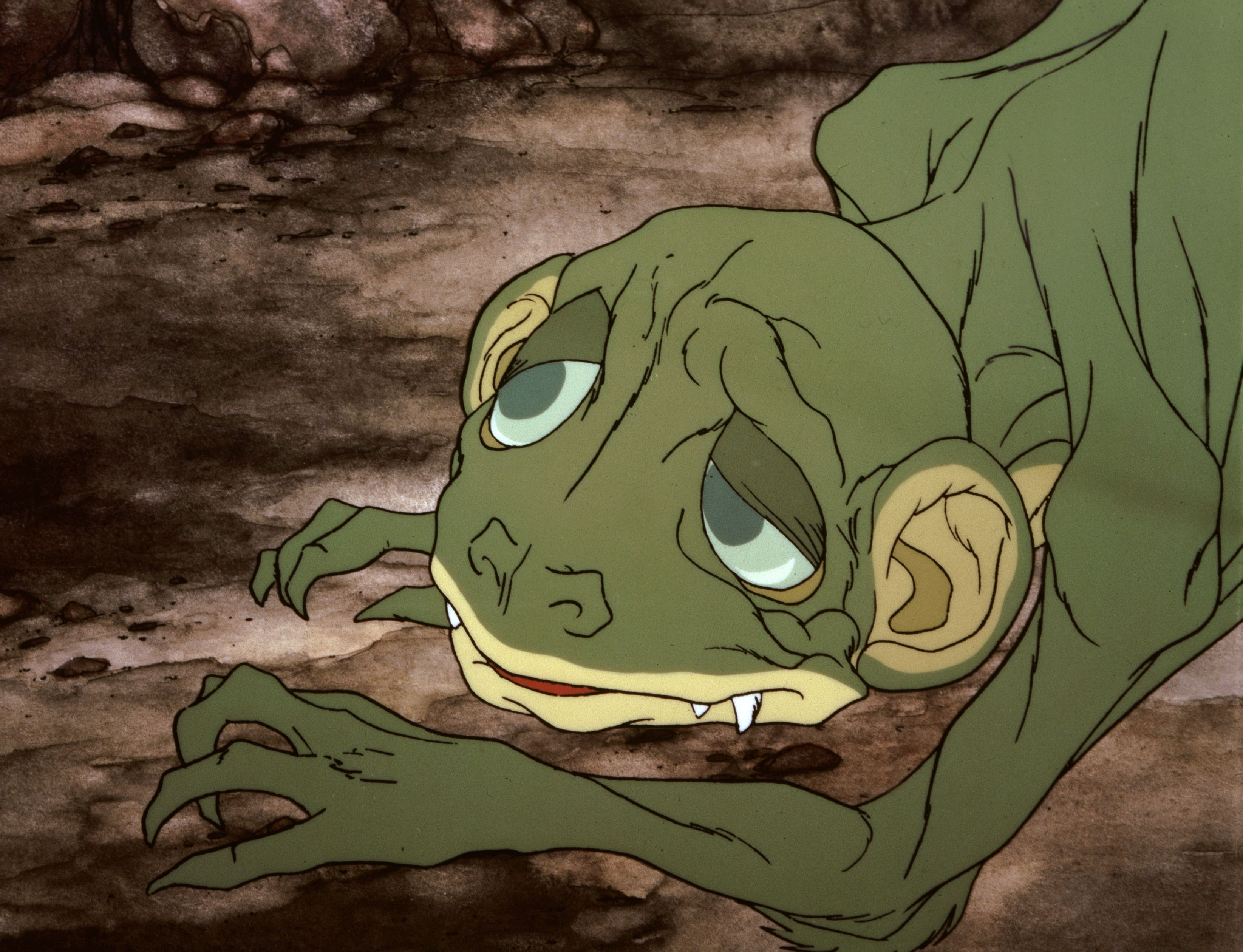

Whether this makes The Hobbit an anime film is debatable. John Culhane of the New York Times reported that Arthur Rankin created the movie’s conceptual art. However, Tor.com contributor Austin Gilkeson suggests the cat-like rendering of Smaug shows Eastern animation intersecting with Western. Viewers get a dragon envisioned by a Western artist, but animated by artists with no background in European folklore.1

Anime or not, The Hobbit does show one thing: in a time when few fantasy movies were blockbusters, audiences’ idea of what a dragon was supposed to look like hadn’t been canonized yet.

Given its unusual look, this movie may experience a new life soon. The upcoming release of the anime film The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim may bring a more Eastern flavor back to Tolkien animation, leading some to reappraise this movie.

The Return of the King (1980, Directed by Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass)

Some fans may wonder why Rankin-Bass adapted the prequel and end of the Lord of the Rings storyline, but not the middle sections. Fans have suggested several theories, including claims that Saul Zaentz owned the rights to The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers at the time, or that Rankin and Bass learned Ralph Bakshi (whose work will be discussed next in the series) was adapting those two stories. However, Arthur Rankin Jr. gave a more pragmatic reason in a 2003 interview: he worried that audiences would not tolerate a story with such a long running time. “I didn’t know that the audience would sit still for it. I was wrong.”

While the Rankin-Bass adaptation of The Hobbit has its moments, the Rankin-Bass adaptation of Return of the King disappoints.

It has its good moments. It covers the book’s main plots in a compact form, the animation is decent, and the acting is good.

However, the movie takes a large false step by trying to emulate the atmosphere of the studio’s earlier Tolkien film. The Hobbit and The Return of the King fit into the same fictional universe, but the books have significant tonal differences.

Tolkien’s book The Hobbit is very musical—from the singing dwarves at Bilbo’s house to the singing goblins to the singing Rivendell elves. While dark at times, there’s a playfulness throughout, making it a children’s fairytale rather than an epic.

In contrast, The Return of the King shows how much Frodo’s quest has become the opposite of Bilbo’s treasure jaunt. The Fellowship of the Ring starts out playful with a grand birthday party. It has its gentle or jolly moments, like Tom Bombadil meeting the hobbits or the singing elves passing through the Shire (both discussed in the previous post on this series). But, even in this first book, Frodo talks about how his journey is becoming something very different than the journey Bilbo took. By the time he is in Mordor, that has become very clear. There is little music, comedy, or playfulness in this hard, grueling last act.

The often-cited point that Tolkien inverted Macbeth’s final plot twist to create the scene of Eowyn killing the Witch-king of Angmar sums up the difference rather well. Like Shakespeare’s Scottish play, The Return of the King is a tale of anger, blood, and feuds exposed. Rankin-Bass’s attempt to lighten things by adding songs and a children’s animation style (note, for example, the childish-looking Witch-king, who looks like something from a He-Man cartoon) fall flat.

The attempt to take such a dark story and make it something for kids also speaks to a misconception especially common at the time: that all fantasy is kid’s stuff, so a fantasy movie should necessarily be lighthearted.

Footnote: I’m not the first to make this suggestion about Rankin-Bass’ work. Constantine Nasr’s 2018 documentary The Animagic World of Rankin/Bass discusses the company’s Christmas specials. Interviewee Jerry Beck observes that Japanese stop-motion animators did the actual animation on those specials, and he often tells his California Institute of the Arts students that those films meant Japanese animation influenced them earlier than they thought.

Come back next week when we discuss The Lord of the Rings directed by Ralph Bakshi.