Tolkien Before Jackson Part 2: Lord of the Rings (1971, directed by Bo Hansson)

Fans of The Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit frequently mention Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 movie or the Rankin-Bass 1977 The Hobbit (both of which will be discussed later in this series). Since Gene Deitch’s 12-minute version of The Hobbit was rediscovered in 2012 (see previous post in this series), various people have discussed its attributes.

As of this writing, far less has been said about a Swedish TV film that manages to be nothing like any of these projects.

Sagan om Ringen is a two-part film (28 minutes total) which appeared on Swedish TV channel SVT1 in 1971. It was directed by Bo Hannson, and inspired by his 1970 instrumental rock album Music Inspired by the Lord of the Rings.

A narrator talks continuously during the twenty-eight minutes while actors perform against painted backgrounds. While the actors are seen talking, the narrator says all their lines. The effect resembles one of those history docudramas shown in school where actors pantomime their performances on sets while the narration fills in the important details.

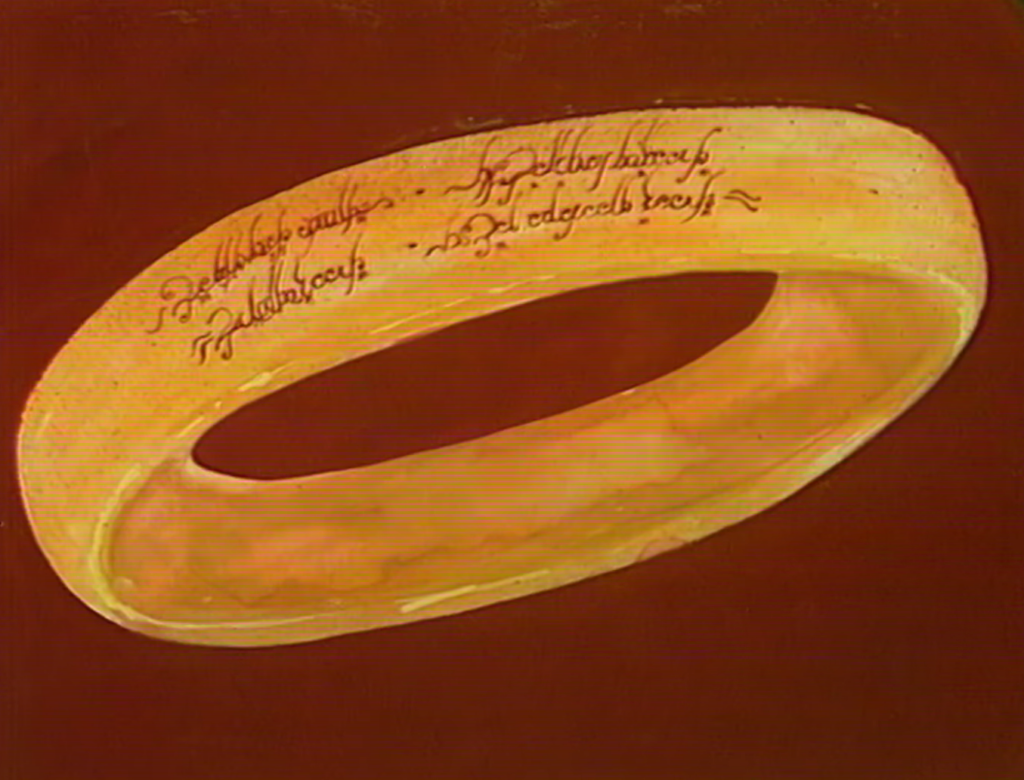

Since the film’s total running length is just under half an hour, it can’t tell the full story of Lord of the Rings. Rather than taking Dietch’s approach and boiling the story down until things become unrecognizable, it covers a subsection of the books. The story starts with Bilbo’s party and ends with the fellowship leaving Rivendell to destroy the ring. For reasons unclear, the ring prop is the size of a large soup bowl.

The narration approach means there are few conversation scenes. Ultimately, the acting never quite complements the narrator: their acting has a hint of pantomime, but not the over-the-top pantomime that makes silent films like Fritz Lang’s Siegfried films so much fun. While the narration with silent actors may not be particularly cinematic, it is efficient. Since the story doesn’t have to stop for dialogue, events can move quickly, covering half of The Fellowship of the Ring in just under 30 minutes.

At the same time, the script takes time for little moments. The narration contains bits of dialogue straight from the book—Gandalf sharing the ring’s history, Frodo and his friends meeting wood elves, Gandalf sharing how he got Shadowfax—without much trimming. The story also takes time to include a dance sequence when the wood elves are camping out with Frodo. Tom Bombadil makes an appearance to rescue Pippin from Old Man Willow (although Goldberry and the Barrow-wights never appear).

In other words, this Swedish Lord of the Rings leaves a great deal out, yet slows its pace to include the scenes that most adaptations omit.

The choice to cover little incidental scenes that don’t move the plot forward may indicate an inefficient script, but it highlights something important. Tolkien didn’t just write a huge story; he wrote a huge story where he seemed equally invested in the little things—the offhand references to past events, the traveling scenes, the elves’ songs—as he was in the broad character arc. Consequently, he is a particularly hard author to adapt. Screenwriter William Goldman observed in his book Five Screenplays that you can change and improve a script, as long as you have identified the story’s spine and trim things that won’t damage the spine. The same applies to adapting a book—a movie may be very different from the book, but it will still work if it doesn’t break the original story’s spine.

Some fantasy authors make this process easier than others. Fantasy authors like J.K. Rowling give their fantasy worlds depth but keep the plot in the foreground. The Harry Potter movies lose something by leaving out subplots about how side characters fell in love or how villains escape from magic prisons. Still, they maintain the core story (Harry fighting Lord Voldemort) fairly well. Rowling keeps the plot front and center. Tolkien wrote stories in which the plot, the secondary details, and the backstory each feel loved and important. This Swedish TV film shows that whatever fans may think about omitting Tom Bombadil or the Scouring of the Shire, every choice to change Tolkien’s text is unusually tough.

You can watch part 1 and part 2 of the movie for free at the links below:

Come back next week as we look at the 1977 Rankin-Bass adaption of The Hobbit.