Tolkien, Anglo-Saxon England and the Viking exhibition at the British Museum

Much has been made of a civilization lost in the mists of time – the Vikings. When they first made their appearance in 793 AD, plundering Lindisfarne Priory where the beautiful Lindisfarne Gospels are said to have been made, they started on a conquering expedition throughout all of Europe. Luckily enough, their image of murdering, pillaging heathens has slowly been changing to a more comprehensive view of a conglomerate of different peoples made of traders, diplomats, artisans and warriors whose success is based on an advanced piece of technology they had invented: the Viking longship. Roskilde 6 is now prominently displayed at a major British museum exhibition together with other findings from Anglo-Saxon England for the first time and definitely worth a visit.

A.D. 793. This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery, dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island, by rapine and slaughter. [Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, my emphasis]

One of the treasures to be seen is the Vale of York hoard, a collection of several hundred coins and other items from the 10th century. Parts of it come from Samarkand in central Asia, Afghanistan, Russia and North Africa which will give you an idea how far-reaching the trading network of the Vikings had become by that time. The British Museum notes: “The hoard was probably buried for safety by a wealthy Viking leader during the unrest that followed the conquest of the Viking kingdom of Northumbria in AD 927 by the Anglo-Saxon king Athelstan (924-39). This was a key moment in English history, with the whole of England brought under one king for the first time. However, the hoard provides interesting evidence that the process was not as smooth as the official record produced at Athelstan’s court suggests.”

J.R.R. Tolkien was Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor in Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College from 1926 until 1945. A linguist by profession he had to be widely read in other fields such as archaelogy which was providing new material on Anglo-Saxon England during his time as an active academic and he took a special interest in the fate of the sea-faring peoples conquering England after the withdrawal of Roman soldiers in the 4th & 5th century. His posthumously published work on Finn and Hengest: The Fragment and the Episode (1983) shows how he understood parts of the early Landnahme of England by Anglo-Saxon mercenary foederati was supposed to have happened. [Please bear in mind that terms such as Anglo-Saxon and England are generalisations which have to be used with caution as their meaning is open to change according to context.]

In a 1945 letter to his son Christopher Tolkien wrote: “For barring the Tolkien (which must long ago have become a pretty thin strand) you are a Mercian or Hwiccian (of Wychwood) on both sides.” The Kingdom of Mercia which existed roughly from 600-900 AD was one of the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which was destroyed following the Viking incursions into England and the founding of the Danelaw. Tolkien was a specialist in the Mercian dialect of Old English and used parts of it to represent the Kingdom of Rohan in The Lord of the Rings (the Mark being cognate with Mercia) as Tom Shippey noted in The Road to Middle-earth.

So if you want to get a feel of the Vikings, Anglo-Saxon England, the Riddermark and how the Corsairs of Umbar (?) sped up rivers to attack cities in Middle-earth or get an idea of how great warriors and kings were buried in their ships (Boromir wasn’t the only one) you should possibly have a look at the new exhibition space at the British Museum for Vikings: life and legend. If you can’t make it to London right now (the exhibition opened only yesterday) you should come to Berlin and visit it together with the Tolkienist – it is organised by the British Museum, National Museum of Denmark and the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. And as such it will be shown from September onwards at the Martin Gropius Bau.

If you want to know what the Vikings could do with their longships have a look at this long video clip about the longship reconstruction project, the Sea Stallion of Glendalough, which travelled from Denmark to Ireland in 2007/2008 and proved how sea-worthy those ships were. [A reconstruction of the Skuldelev 2 ship.]

- Penrith Brooch, c.900, from near Penrith, Cumbrian, England. Silver. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Sword, late 8th–early 9th century. Kalundborg or Holbæk, Zealand, Denmark. Photo: John Lee. © The National Museum of Denmark.

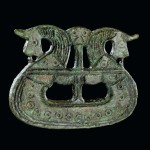

- Brooch shaped like a ship, 800-1050. Tjørnehøj II, Fyn, Denmark. Copper alloy. © The National Museum of Denmark

- Odin or völva figure, 800-1050. Lejre, Zealand, Denmark. Silver with niello. Photo: Ole Malling, Roskilde Museum

- Lewis Chessmen 1150-1145 © The Trustees of the British Museum

- Silver-inlaid axehead in the Mammen style, AD 900s. Bjerringhøj, Mammen, Jutland, Denmark. Iron, silver, brass. L 17.5 cm. © The National Museum of Denmark

Quote. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Taken from Gutenberg.org. Mercian: The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (ed. Humhprey Carpenter), 1981: Letter #95.

Picture credits. Featured image: The installation of Roskilde 6 at the British Museum in the Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery, January 2014 © Paul Raftery. The Vale of York hoard, AD 900s. North Yorkshire, England. Silver-gilt, gold, silver. British Museum, London/Yorkshire Museum, York. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Penrith Brooch, c.900, from near Penrith, Cumbrian, England. Silver. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Silver-inlaid axehead in the Mammen style, AD 900s. Bjerringhøj, Mammen, Jutland, Denmark. Iron, silver, brass. L 17.5 cm. © The National Museum of Denmark. Lewis Chessmen 1150-1145 © The Trustees of the British Museum. Odin or völva figure, 800-1050. Lejre, Zealand, Denmark. Silver with niello. Photo: Ole Malling, Roskilde Museum. Brooch shaped like a ship, 800-1050. Tjørnehøj II, Fyn, Denmark. Copper alloy. © The National Museum of Denmark. Sword, late 8th–early 9th century. Kalundborg or Holbæk, Zealand, Denmark. Photo: John Lee. © The National Museum of Denmark.

In 1992, shortly before the Centenary Confrence (for which reason I made my first and thus far only trip to the UK), I stood in the ruins of Lindisfarne Priory and declaimed that very passage from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, in Old English (which I’d studied for some years in college). Seems a lifetime ago now, but I’ll never forget it!

It is definitely on my “to visit list” for beautiful places in England!

And perhaps I should learn Old English before that 🙂