Introducing the art of John Cockshaw: A different path to Middle-earth

When I first saw John’s art I was amazed at seeing a new approach in representing the creative worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien. His unique mixture of photography and digital retouching seemed to me another convincing proof that art is certainly the one medium best able to show how Middle-earth inspires individuals to bring their interpretations to life. John was kind enough to send me some of his thoughts on his work and how he goes about it.

On a photography-based approach to Tolkien

John, thank you very much for sharing your art with the Tolkienist. Could you tell me how you first learned about J.R.R. Tolkien and his works?

The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R Tolkien featured much in my childhood; it was the solemn, intimidating looking adult book on the bookshelf that my parents had read and the one my brother had tried to read whilst lamenting the fact that the characters sang too much. I had very little need or liking to start exploring it. Not yet, at least. Local amateur dramatic productions and the Ralph Bakshi animated film offered the first brief entries and character introductions into my Tolkien education.

Like many it was the Peter Jackson movies commencing in 2001 that created the awareness and served as a beginning. The way was led then to the BBC Radio adaptation first broadcast in 1981, following simultaneously to the source book – nicely being the same of the book that had lived all this time on the bookshelf waiting.

What strikes me as a fascinating notion, especially when it comes to the forming of a Tolkien-inspired art, is the difference and disparity of different interpretations. The book can be read over again and be experienced differently for one, therefore continuing its capacity for applicability. The radio and cinematic dramatisations of The Lord of the Rings are different beasts to the book and have to undergo a complex set of decisions that involve abridging and embellishing the original text. In this vein I’m fascinated by how other artists choose to depict Tolkien and form their approach based on the text. J.C.

In conjunction with Tolkien’s text it is the influence of the audio presentations of Middle-earth that have most forcefully shaped my artwork, more so than the cinematic interpretations that were a powerful reference at the start of the project – though one of these elements is linked to these. Listening to the Rings BBC Radio drama opened up endless visual possibilities for exploration, as did Rob Inglis’ marvellous unabridged reading which allowed me to feel what it was like on the Barrow Downs more effectively than I felt by solely reading the book. Howard Shore’s film score for The Lord of the Rings plays an important part too; its operatic-like telling of the grand tale becomes an interpretation of Tolkien’s text in its own right. Rewarding and immersive, that I enjoy in the same manner as Wagner’s Der Ring Des Nibelungen, my appreciation of its scope has been expertly enhanced by Doug Adams’ fascinating musical analysis of the score. To cite two examples of this, I’d mention the way the percussive pattern of the Isengard theme develops in The Two Towers to act like a parasite to overwhelm all the other musical material that comes into its path, and the development of themes that graduate from the Third Age to Fourth Age variations by the conclusion of The Return of the King. Shore’s work, in its full 10-hour form for orchestra and chorus impresses in its epic scale, grand glory and the menace of evil times, but it is the softer understated sections where the music really works its magic to my mind and charts the musical landscape of Middle-earth. I hope the scenes of Tolkien I choose to depict as artwork follow such a principle and achieve such an effect.

There are many artists with a ‘conventional’ approach to Tolkien – what made you work with photographs and digital retouches?

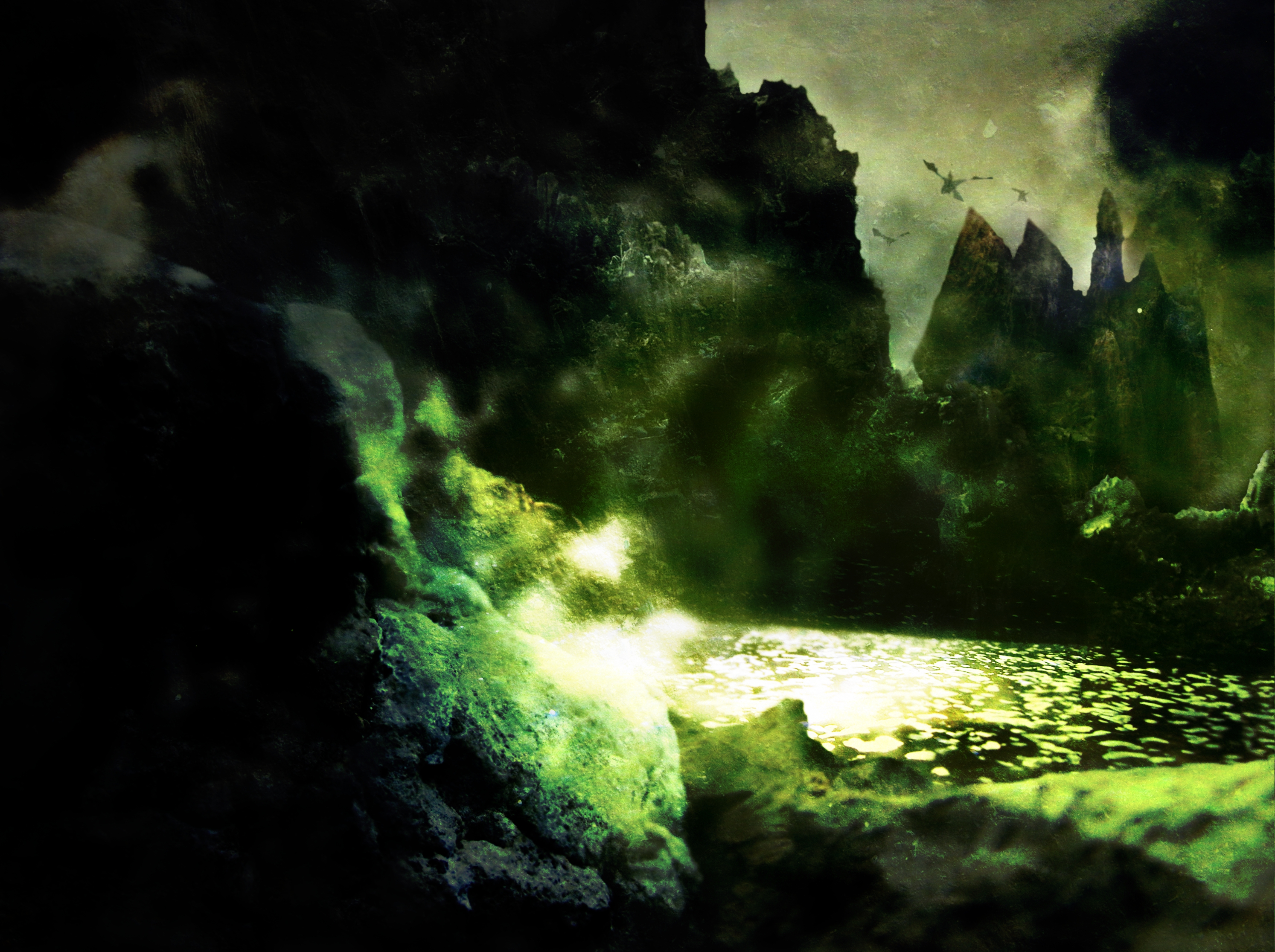

The reasoning for using photography and digital manipulation to explore Tolkien-inspired art is two, even three-fold. Firstly, and simply, my painting style leans more to impressionism and techniques of abstraction. That isn’t to say it doesn’t offer a means of expressing Tolkien, it just isn’t calibrated towards that aim yet and I’d want to be sure I could offer something that would add something new – and I’d certainly like to reinvent my painting style to approach landscapes of Middle-earth for example. Secondly, it was the close scrutiny of landscape on a miniature scale as if it were a film set that really kick-started this project and macro-photography was the method of this exploration. Thirdly, the philosophy of approach was the key element; the art would make reference to sources of realism through photography and then finished into a combined cinematic/illustrative style without being slavish to photorealism – in essence transforming real photographic reference points into fantasy depictions combining full and miniature scale.

To add to this rationale about my approach, the principle of understatement is important. The art isn’t composed from the most dramatic photographs I could possibly have taken; it’s a case if it being collaged from the more innocuous-seeming photos that I’ve bent to my will in fun and surprising ways through experimentation. I have less of an interest in depicting characters than presenting characters as barely glimpsed pawns in the vast landscape of Middle-earth, and even then the landscape is distanced at about the right point for the imagination to expand what is detected. Suggestion and hinting, by and large, are the rules at play in the work.

The photography also facilitates the location scouting and interaction with landscape that continually reinvigorates my enthusiasm for Tolkien’s writing, which presents the character of Middle-earth in a detailed earthy realism. A well-acquainted Tolkienist won’t need me to point out the wealth of landscape description that expertly maps out Middle-earth. The project allows me to reference my favourite Tolkienesque places and when these are in my home county of Yorkshire implicitly acknowledge Tolkien’s own connection with the county. This connection comes in the form of his Professorship at the University of Leeds notable for his work on the edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight with E V Gordon. There seem to be no strong grounds for any claim upon Yorkshire to have influenced Middle-earth in any way, but my hopeful wish is that its landscape in some small way might have been fondly remembered in the shaping of it.

Could you tell me more about two catchwords you mentioned: archaeology and the Yorkshire Dales?

Of the many impromptu and planned photographing trips that have contributed to the gathering of material for my artwork one in particular has ended up exerting an influence that I could scarcely have known at the time. This was solely down to the company I kept.

During Summer 2009 I accompanied Archaeologist Shaun Richardson deep into the heart of the Yorkshire Dales to Crummackdale where he and a colleague were undertaking to record possible Neolithic landscape elements. I was along for the ride by invitation based on previous conversations about the beauty of our surrounding area. Lo and behold Shaun revealed himself to be a knowledgeable Tolkien enthusiast, not least in the field of Tolkien illustrators of the likes of Pauline Baynes. The site itself echoed of the wolds of Rohan, but the material here contributed some macro photography of stone to help depict what would eventually be Lair of the Wraiths (2012).

He interpreted enticing associations of some of my pieces to the background sections of Bosch paintings, and the sense that there was always much more to discover beyond the frame of the piece. Importantly, he saw ghostly suggestions of characters and action within the art that required the imagination to supply more than was shown; that there was a grand narrative at work only hinted at. J. C.

Shaun’s feedback upon first seeing my work supplied all the encouragement I needed and more. Furthermore he made interpretations and readings on the pieces drawing on his archaeological knowledge and area of study that drew on medieval viewing practices in terms of architecture and notions of perspective when viewing landscape. The crucial thing for me; it seemed there was a good basis upon which an academic weight could be brought to bear on the work – give it a good bit of substance to compliment my own thoughts and rationale. There is nothing more gratifying for an artist to receive such unexpected readings and interpretations of their own work. I’m thrilled that Shaun agreed to provide an introductory text to the upcoming book Wrath, Ruin and a Red Nightfall that expands upon these briefly mentioned points and more.

On landscapes, visuality and contemporary perceptions

Shaun Richardson stresses the importance of appreciating “buildings within their landscape settings and trying to understand how past visuality impacted upon the understanding of these buildings and landscapes by contemporaries.” It is this shared interest in “how landscapes are / were perceived by those travelling through them on foot” which has led to this fruitful cooperation.

For further reading please have a look at three of Shaun Richardson’s articles.

Richardson, S. 2005. Welcome to the Cheap Seats: Cinemas, Sex and Landscape, Industrial Archaeology Review, 27(1), 145-152.

Richardson, S. 2008. Destruction Preserved: Second World War Public Air-Raid Shelters in Hamburg, in L. Rakoczy (ed.) The Archaeology of Destruction, 6-28, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

Richardson, S. 2010. A Room with a View? Looking Outwards from Late Medieval Harewood, The Archaeological Journal, 167, 14-54.[/learn_more]

John Cockshaw’s Middle-earth inspired artwork has had a long period of development, which is wholly appropriate when approaching on author’s work that is as revered and dissected as J.R.R Tolkien’s. It would be foolish not to, nor for any artist to treat it lightly. The rewards of discovery and the ongoing fascination to be had from the source material is an intoxicating prospect, endlessly fascinating. The fruition of his planning, which even now is still ongoing, resulted in the first round of finalised pieces in his art collection ‘From Mordor to the Misty Mountains’ in September 2012

Pieces from the collection will form the art volume ‘Wrath, Ruin and a Red Nightfall’ from Oloris Publishing in 2014. Find out more about his art at his official blog.

Thanks for posting this very interesting and thoughtful article/interview. The following comment isn’t meant to be a criticism, just a slight correction. At one point John says: “There seems to be no strong claim upon Yorkshire to have influenced Middle-earth in any way. ” Whilst I can’t comment upon the landscape of North and West Yorkshire, I would like to point out that East Yorkshire does have a strong claim to have influenced one of the most important and enduring tales of Middle-earth. There can be little doubt that the ‘hemlock’ glade in Roos and what happened there had a significant influence on one of the central tales in Tolkien’s imagination & writing career. Yorkshire is a massive county, and because East Yorkshire is the least populated, and is ‘out-on-a-limb’, it is understandably often forgotten or ignored. However, in this specific instance I would argue it does have a claim to be remembered as having influenced one aspect of Middle-earth. No offence intended to John’s very interesting views.

Michael, thank you for noting this. You are, of course, right in mentioning this! My only apology is that -as I am not from the UK and am not that familiar with all of its landscapes- I did not immediately see the link Yorkshire -> Roos.

However, this is what this comment section is about – to improve on the articles posted here. Thanks again!