75 reasons: David Bratman

Nearly a dozen years ago, a few months before Peter Jackson’s Fellowship of the Ring hit the big screen, a wise comment about it was made … in a web comic. Scott Kurtz’s PvP ran a strip in which a young character who’s never read The Lord of the Rings is told by his more experienced boss to read the book now, “before the movie. … Don’t let the movie create the first images of these characters for you.”

They were wise words then, and they’re wise words now about The Hobbit. You only have one chance to read a book for the first time. A popular movie becomes ubiquitous, and Peter Jackson showed with The Lord of the Rings that he had that talent. Even people who haven’t seen the movies have had those images inserted into their imaginations. Right now is the last time in foreseeable history that you’ll be able to read The Hobbit without those images taking over that book too.

“The Hobbit is quite different from The Lord of the Rings in tone and style.”The Hobbit is quite different from The Lord of the Rings in tone and style. It has to be, because in large part it’s the same story. A reluctant hobbit adventurer sets out on a journey eastward, having almost interchangeable semi-comic, semi-horrific adventures on the way, before fetching up in Rivendell to have a big confab with Elrond. After which, the two hobbits set off in different directions, but on similar errands: mad, seemingly imposible quests.

But the one story doesn’t feel repetitive after the other, and one major reason it doesn’t is the difference in tone. After The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings is a bigger, darker book, with a broader, deeper view of the world it’s set in. It’s harder, though, to turn back from The Lord of the Rings to The Hobbit. Tolkien himself grew a bit embarrassed by the earlier book’s lighter tone, and attempted a thorough rewriting more in the style of The Lord of the Rings. But he soon abandoned it, for just that reason – it would repeat what he’d already done. (You may find the relics of this draft in John D. Rateliff’s estimable The History of the Hobbit.)

What can we judge of the Hobbit movie from the trailers, though? A trailer is not its movie, but the trailers of the Lord of the Rings movies gave pretty good indications of the final product’s nature. And you will see many comments online expressing enthusiasm for the upcoming movie based on its trailers, so if they can feel pumped, I can with equal justification express caution based on the same evidence.

Jackson has decided, perhaps inevitably in the circumstances, to frame The Hobbit as a prequel to The Lord of the Rings – that is, a story told later though taking place earlier – and he has given it the tone of the other book, or, more precisely, of the other movies. Everything said in the trailer about the possible dangers and how the journey will change Bilbo is in the book in some way or other, but the feel is entirely different. In Tolkien’s books, Frodo sets out with a miasma of danger already hanging over him – one which Jackson, typically, overplays, not knowing the difference between danger and action – but Bilbo rushes out in a whoosh of comic spirit, and his growing misery is based merely on physical discomfort. He knows there’s a dragon ahead, and probably other dangers on the way, but he’s not thinking about them because he can’t even imagine them. They don’t hang over the story. Everything hangs over this trailer. The dark ominous tone in which Jackson’s Thorin refuses to guarantee Bilbo’s safety, whereas in the book a more general warning is comically embedded in a pompous speech, the equally ominous shot of the Ring, whereas it’s essential to the tone of The Hobbit that the Ring not have all the baggage that would be piled on it in the sequel.

Will the movie be good, or bad, or some mixture of the two? I don’t know at this point, and neither do you, but one thing is clear: it will be different from the tone of the book, and more like that of The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbit is its own book, and should be judged on its own merits, which are considerable, and different from those of its sequel. My own first encounter with Tolkien was at the age of eleven with The Hobbit. I was enchanged by the vividness of the prose and storytelling, the integrity and color of the characters, and above all by the vastness of the uncharted vistas that the story threw open. It begins with no portentious burden of backstory, but simply with a hobbit – and what a hobbit might be is carefully explained by the narrator – sitting on his doorstep smoking a pipe. From this simple and unimposing opening, the reader is sucked in to a story with more seriousness and weight than would at first have seemed possible.

If you haven’t read it, read it now. While reading it, ignore the movie, while you still can. Ignore Tolkien’s other books, too, if you can, and enjoy The Hobbit for what it is: the grandest of all children’s fantasy adventure tales.

David Bratman

Author biography

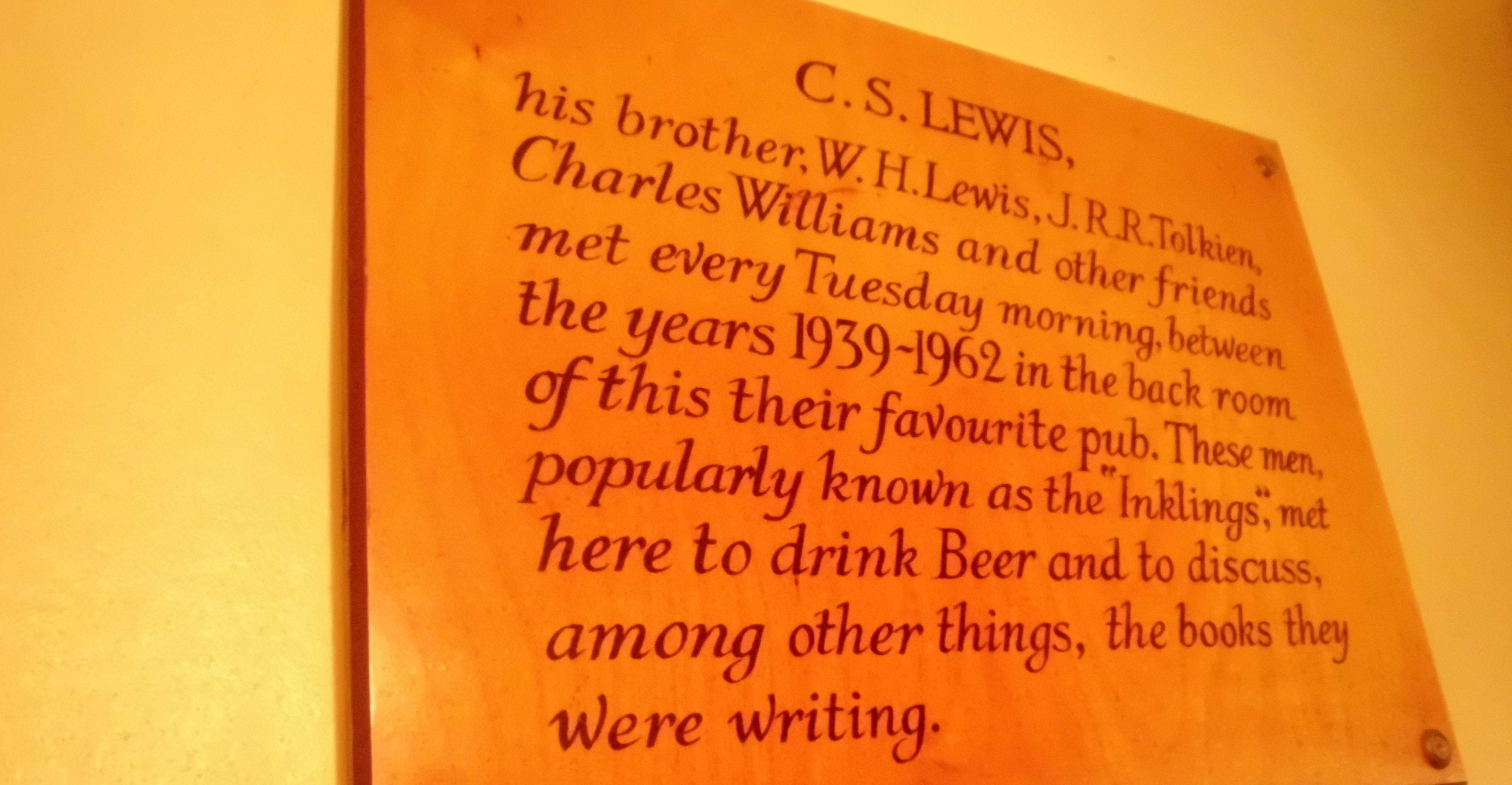

David Bratman has been puttering around Tolkien studies since being the first person to publish a Tale of Years for the Elder Days a month after The Silmarillion appeared in 1977. Since then he’s been editor of Mythprint for the Mythopoeic Society, author of “The Year’s Work in Tolkien Studies” for the journal Tolkien Studies, and author also of articles on textual revisions in The Lord of the Rings, on the road through The History of Middle-earth, on the geography of Tolkien, on music and Tolkien, and on the history and personnel of the Inklings.

When not Tolkiening, he’s a librarian and an arts critic. He lives in California with his lawfully wedded soprano and two cats.